Little Head-Bob woke up. He could hear the wind through the oaks and the cedar trees. He could feel a draft coming in the hole to the nest. Spring here, his first, was still a little chill in the mornings. He was warm though, huddled up with all his brothers and sisters so close. His mother’s silent appearance with a still warm squirrel was met with enthusiastic hoots and rasps from four different adolescent beaks.

Just out the hole in the oak, where where

they all sat digesting, was the remains of another oak, worn by weather

and eaten by termites. There was little left but a ring of bare trunk

about as tall as an owl, and one almost flat side rising to about the

height of a buck’s shoulder. The outer surface of this side, bark long

gone, showed something else that fascinated Head-Bob, something he had

never seen anywhere else.

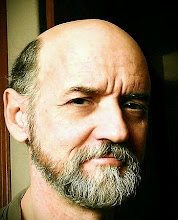

It was the face of a man, prominent nose, eyes set deep under heavy brow and staring up, directly at the entrance to the nest. Little Head-Bob had never seen a man. All he knew was that this face, so different to him, was of something strong and fierce. Perhaps it was a spirit, some guardian of the woods , perhaps one of those he heard sighing and whispering in the night.

It was the face of a man, prominent nose, eyes set deep under heavy brow and staring up, directly at the entrance to the nest. Little Head-Bob had never seen a man. All he knew was that this face, so different to him, was of something strong and fierce. Perhaps it was a spirit, some guardian of the woods , perhaps one of those he heard sighing and whispering in the night.

On the far side of the small woods, other

beaks were raising more raucous voices, grating and challenging. They

changed the feeling of the woods and indeed the air itself. The Murder

of Crows was awake and casting about for whom, as they say, it might

devour.

Though it was normally his family’s habit

to stay in the nest most of the day, they did sometimes go out into the

limbs of their tree to watch and to listen to their woods.

With his keen ears he could hear the distant sound of the crows. He had never seen a crow either, but he had heard them calling through the woods. He somehow knew their strident voices, heard first from this way and then that, meant nothing good. Still, he wondered just what all that noise was really about.

With his keen ears he could hear the distant sound of the crows. He had never seen a crow either, but he had heard them calling through the woods. He somehow knew their strident voices, heard first from this way and then that, meant nothing good. Still, he wondered just what all that noise was really about.

Perhaps today was a good day to go for a

little flight. As he hopped to the edge of the limb and pushed off into the air he heard his brother and sisters rasping and calling in dismay at

his abrupt departure. he stopped in a nearby persimmon tree to watch

the remarkable progress of a tortoise crashing loudly through the

remnants of last year’s dead leaves. He wondered how something so like a

rock moving at such a slow pace could make so much noise.

He continued on across the wood, thinking

about the tortoise, he had forgotten about the crows. As he flew on,

suddenly there was a crow, another entirely new thing to him, flapping

from limb to limb, all the time cawing more and more loudly and

alarmingly. Another crow, then another, and another until Little

Head-Bob was surrounded by many crows, diving at him, hopping along the

nearest branches as though in mock attack.

He hissed. He flapped and spread his wings in warning display. The crows were not impressed or frightened. He dove out of the tree, right at two crows nearest, but they were too fast, to agile for him to touch. And still as he tried to get away from them, away from their noise, the crows pursued.

He hissed. He flapped and spread his wings in warning display. The crows were not impressed or frightened. He dove out of the tree, right at two crows nearest, but they were too fast, to agile for him to touch. And still as he tried to get away from them, away from their noise, the crows pursued.

Little did he know, but would soon

discover, he had just met his second greatest enemy and possible

nemesis. It was not uncommon for an owl to be continually and

relentlessly harassed and pursued, both day and night, until unable to

sleep or to hunt the owl would weaken, succumb and die. The crows had a

system. They had numbers. They could, by working is shifts, keep up

their siege well beyond the strength of any one bird to match. As the

day wore on Head-Bob learned, bit by bit, of the nature of crows.

As he perched, his back up against the

trunk of the tree, hissing and snapping at the crows, he began to pick

up another sound. Some other unknown creature, was making its way into

the woods. Though most of his attention was on the jeering crows, he

could still track the sounds of the new thing enough to realize it was

coming directly towards him. Was this, he wondered some new foe, taking

advantage of his vulnerability to end his short life?

But when the creature emerged from a copse

of cedars The young Great Horned Owl saw something he never would have

expected, even more remarkable the murder of crows. It was a large

thing, walking on two legs, covered in something not fur, not feather,

nor even scales. It carried in its upper limbs something even more

remarkable, a long shiny thing that smelled of fire, some mineral, and

somehow, some new definition of death.

As Little Head-Bob perched, his back

against the trunk of the tree, transfixed by the shear strangeness of

the thing below, it did a new thing. It turned its head and, staring

him straight in the eye, showed him its face, showed him the face in

the woods. It was the face he had seen all his life, carved in the stump

by his nest.

The thing looked at Head-Bob. It looked at

the crows. It looked at Head-Bob, and again at the crows, and then at

the thing it carried. Its face, as it watched the crows, took on a

harder even more intimidating cast. It raised the thing and pointed it

at the crow nearest to Head-Bob. He saw it hopping towards him on the

limb above his. The world exploded. It ended with the sound and the fury

of a thousand thunder claps.

The young owl sat up in the grass below, the crow lay dead a small way in front of him. The rest of the crows had taken off, but hadn’t gone far. They were mumbling now in the next tree, to themselves, or the owl, perhaps to the man.

The man spoke, another new thing. He spoke to the crows. He spoke to the owl.

The young owl sat up in the grass below, the crow lay dead a small way in front of him. The rest of the crows had taken off, but hadn’t gone far. They were mumbling now in the next tree, to themselves, or the owl, perhaps to the man.

The man spoke, another new thing. He spoke to the crows. He spoke to the owl.

“You no-good sons a bitches are gonna learn

to leave my owls alone! And you, young feller, better get back to

Mommy and Daddy while I instruct these miscreants and your gettin’ is

good.”

Little Head-Bob stayed crouched where he was, unable to move.

The man, the Spirit of the Woods, waited

one – two – three breaths.

“I mean leave! Now! And do try to pay attention to who’s around next time, would you?”

“I mean leave! Now! And do try to pay attention to who’s around next time, would you?”

Little Head-Bob jumped into the air and

flew faster than he had ever flown. Behind him the sound of a thousand

thunders came again, and again, and once more. He went straight back to

his own tree, back to his nest. He buried his face under his wing,

overcome by too much fear and too much amazement, over the crows, over

the man, the face in the woods.

Bob woke up. He looked around him at the

cold dead remnants of last night’s camp fire. He looked at the sandstone

before him there on top of the hill at the edge of the woods.

Everything seemed different, more serious, and more miraculous than he

had ever seemed to feel before. He had no idea why. There was something,

some feeling … he just couldn’t remember.

He got up, rolled his sleeping bag and started off towards the house. He wanted coffee, that first, best cup of the day. He thought he might get his tools, go back up into woods today, work on that carving of his father’s face. The one he hadn’t seen in too long.

He got up, rolled his sleeping bag and started off towards the house. He wanted coffee, that first, best cup of the day. He thought he might get his tools, go back up into woods today, work on that carving of his father’s face. The one he hadn’t seen in too long.